Влияние маркетинговых стимулов на потребителя

Введение

потребитель маркетинговый стимул

Актуальность темы исследования. Изучению потребителей

отводится важное место в маркетинговой науке и практике. Фирмы вкладывают

значительные ресурсы в исследования особенностей восприятия и оценки

потребителями рыночных предложений, а также их поведения на рынке. Понимание

данных аспектов позволяет фирмам предпринимать стратегические и тактические

действия, обладающие большей убедительностью для потребителей и, как следствие,

большей эффективностью для самой фирмы. Потребители, подобно фирмам, также

накапливают информацию и знания о рынке и механизмах его функционирования через

личный опыт взаимодействия с рынком, средства массовой информации или другие

источники. При этом имеющиеся у потребителей знания об используемых фирмами

инструментах воздействия во многом определяют последующую реакцию потребителей

на маркетинговые стимулы и поэтому представляют непосредственный интерес как с

практической, так и с теоретической точки зрения.

Исследователями было неоднократно доказано, что потребители,

обладающие различным объемом и содержанием знаний об используемых фирмами

маркетинговых инструментах воздействия, по-разному реагируют на маркетинговые

стимулы, с которыми они сталкиваются на рынке. В частности, при контакте с маркетинговым

стимулом реакция потребителя на данный стимул будет обусловлена тем,

воспринимает ли потребитель его как намеренную попытку воздействия со стороны

фирмы, или, выражаясь иначе, осознает ли он воздействие маркетингового стимула.

Осознание воздействия маркетингового стимула влечёт за собой изменение реакции

потребителя на данный стимул.

Особый интерес представляет собой изучение роли осознания

потребителями воздействия со стороны фирмы при взаимодействии с маркетинговыми

стимулами, которые потенциально могут ввести потребителя в заблуждение. Феномен

«введение в заблуждение» имеет место тогда, когда представления потребителей о

том, «как должно быть» не сходятся с тем, «как есть» в действительности.

Примером маркетинговой тактики, которая может ввести потребителя в заблуждение,

является уменьшение размера продукта (package downsizing). Данная тактика часто

используется фирмами, чтобы «скрыть» увеличение цены продукта: вместо открытого

увеличения цены за упаковку продукта, производители уменьшают количество

продукта в упаковке так, что цена за упаковку продукта остается на прежнем

уровне. При этом цена за единицу веса или объема продукта увеличивается.

Потребители в силу многих причин часто не обращают внимания на вес упаковки

продукта и не осознают того факта, что цена за единицу веса или объема продукта

увеличилась. Таким образом, они продолжает приобретать продукт, что,

несомненно, является благоприятным фактом для фирм, практикующих подобные

маркетинговые тактики, но неблагоприятно сказывается на благосостоянии самих

потребителей.

Однако потребители не находятся «в вакууме» и постоянно

накапливают знания о маркетинговых инструментах, используемых фирмами, на

основании собственного опыта или внешней информации. Таким образом, со временем

потребители в большей степени склонны осознавать воздействие на них

маркетинговых стимулов. В связи с этим представляется актуальным изучение того,

как осознание потребителями воздействия со стороны фирм влияет на реакцию

потребителя на различные маркетинговые стимулы и уменьшение размера продукта, в

частности.

Степень разработанности проблемы. Интерес к изучению

феномена осознания потребителями воздействия со стороны фирм постоянно

усиливается, что подтверждается растущим количеством исследований в данной

области. Существующие исследования затрагивают широкий спектр маркетинговых

стимулов, используемых в области рекламы, ценообразования, связей с

общественностью, прямых продаж, управления брендами, ритейл-маркетинга и др.

Исследования тактики уменьшения размера продукта (package downsizing)

представлены в крайне ограниченном количестве в академической литературе по

маркетингу. Существуют исследования, в которых доказывается, что уменьшение

размера продукта оказывает позитивное влияние на прибыльность фирм. В то же

время, есть исследования, согласно которым уменьшение размера продукта может

иметь негативные последствия для фирм в условиях, когда потребители осознают,

что упаковка продукта была уменьшена, что проявляется в ухудшении репутации

фирмы в глазах потребителей, снижении покупательских намерений в отношении

продукта и распространении негативной информации о фирме, использовавшей данную

тактику. С учетом высокой актуальности вопроса для российского рынка, а также

его ограниченного развития в существующей литературе была сформулирована цель

исследования.

Целью исследования является изучение

влияния, которое оказывает осознание потребителем воздействия со стороны фирмы

на формирование реакции на уменьшение размера продукта в контексте российского

рынка.

Для достижения указанной цели были поставлены следующие задачи

исследования:

) Изучить сущность феномена «осознание воздействия» с

позиции существующих теорий потребительского поведения;

) Определить степень разработанности вопроса осознания

потребителями воздействия маркетинговых стимулов в контексте уменьшения размера

продукта;

) Эмпирически протестировать, как осознание

воздействия со стороны фирмы влияет на реакцию потребителя на уменьшение

размера продукта;

) Разработать практические рекомендации по применению

полученных в рамках исследования выводов в управленческой практике.

Объектом исследования является реакция

потребителей на уменьшение размера продукта.

Предметом исследования является роль осознания

воздействия маркетинговых стимулов в формировании реакции потребителя.

Структура исследования подчинена поставленным

задачам. В первой главе производится теоретический анализ феномена «осознание

воздействия» с позиции существующих теорий потребительского поведения. Во

второй главе определяется степень разработанности вопроса осознания

потребителями воздействия маркетинговых стимулов в контексте уменьшения размера

продукта, реализуется эмпирическое исследование и разрабатываются практические

рекомендации.

Теоретическую и методологическую базу

исследования составляют работы российских и зарубежных авторов в области теории

маркетинга, маркетинговых исследований, поведения потребителей и

поведенческой экономики. При проведении исследования используются общенаучные

методы познания и методы статистического анализа.

Информационная база исследования включает в себя

результаты экспериментального исследования потребителей.

Основные результаты работы. В данной работе

предпринята попытка рассмотреть феномен осознания потребителями воздействия

маркетинговых стимулов, объединив различные его аспекты в единый концептуальный

конструкт, а также систематизировать его факторы и последствия. Проведенный

обзор существующих исследований показал, что, когда потребитель интерпретирует

маркетинговый стимул как намеренно инициированную фирмой попытку воздействия,

то он, во-первых, более критически оценивает его, препятствуя тому, чтобы

маркетинговый стимул произвел «задуманный» эффект, и во-вторых, изменяет свои

оценочные суждения относительно связанных с попыткой воздействия продуктов или

фирм. Сформулированные на основании проведенного обзора литературы заключения

протестированы на примере тактики уменьшения размера продукта (package downsizing) в контексте российского

рынка. Результаты исследования демонстрируют, что уменьшение размера продукта

может быть выгодной с точки зрения сохранения продаж тактикой, но может

привести к репутационным потерям в условиях осознания потребителями воздействия

со стороны фирмы.

Теоретическая значимость исследования. На основании обзора

существующих теоретических и эмпирических работ, во-первых, раскрывает сущность

феномена осознания потребителем воздействия маркетинговых стимулов и,

во-вторых, обобщает факторы, обуславливающие возникновение феномена, и

последствия его возникновения для потребителей и фирм.

Практическая значимость исследования. С учетом выявленной в

работе значимости осознания потребителями воздействия маркетинговых стимулов

для функционирования фирм, представляется логичной и актуальной рекомендация

включить данный феномен в число изучаемых и постоянно контролируемых

показателей со стороны фирм.

1. Теоретические основы проблемы осознания

потребителем воздействия маркетинговых стимулов

По материалам научного доклада «When

Consumers Activate Persuasion Knowledge: Review of Antecedents and

Consequences». Working Paper # 5 (E) - 2016. Graduate School of Management, St.

Petersburg State University: SPb, 2016.

Companies invest significant resources in

consumer research. Understanding the peculiarities of consumer behavior in the

market allows companies to take strategic and tactical actions that are more

convincing for consumers and, as a consequence, more effective for the firm.

Consumers, like companies, accumulate information and knowledge about the

market mechanisms through personal experience, media exposure or other sources.

A special type of knowledge consumers develop over time is persuasion knowledge

that includes consumer beliefs about marketing tactics used by firms to

influence consumers.in research on persuasion knowledge is constantly increasing,

as evidenced by the growing number of articles in this area (see Appendix 1).

Existing research on the role of persuasion knowledge in consumer response to

marketing stimuli embraces a wide range of marketing tools used in the field of

advertising [Jewell, Barone, 2007], pricing [Hardesty et al., 2007], public

relations [Foreh, Grier, 2003], interpersonal selling [Williams et al., 2004],

brand management [Van Horen, Pieters, 2012], retail marketing [Lunardo,

Mbengue, 2013], and others.spite of the fact that the studies are linked by

common theoretical construct «persuasion knowledge», they are mostly fragmented

and cover different aspects of the construct. Moreover, research results are

quite diverse and there is a need of systematization.purpose of this article is

to develop an integrated model that clarifies the role of persuasion knowledge

in consumer response to marketing stimulus. The article gathers empirical

evidence on the problem of persuasion knowledge activation for the purpose of

further theory development. Firstly, it sheds light on how different aspects of

phenomenon are addressed in the extant studies, and shows how the studies are

connected. Secondly, the author systematizes the antecedents and consequences

of persuasion knowledge activation. Ultimately, future research directions are

highlighted in the article.the first section of the article the author

introduces persuasion knowledge model (PKM) [Friestad, Wright, 1994] as well as

its adaptation to the consumer behavior context. The second section includes

analysis of key concepts related to PKM and their relationships. The third and

fourth sections summarize the antecedents and consequences of persuasion

knowledge activation respectively. The article concludes with possible

practical implications and promising directions for future research in this

area.

Consumer Response to Marketing Stimuli: Persuasion Knowledge

Perspective

Interactions with consumers are the core of

marketing practice. Inter alia, interactions include marketers’ attempts to

persuade and influence consumers using stimulus related to 4Ps [Kotler, Keller,

2012]. Consumer response to this stimulus is dependent upon a variety of

individual and external factors, and persuasion knowledge is one of them.

The term «persuasion knowledge» was firstly

coined in the seminal article by Friestad and Wright [1994]. The authors

positioned persuasion knowledge as a part of a broader model - Persuasion

Knowledge Model (PKM) - that embraces the key elements and mechanisms involved into

persuasion episodes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Persuasion Knowledge Model

(and influence) is a process that involves an

agent and a target. The term «targets» refers to those people for whom a

persuasion attempt is intended (e.g., consumers, voters). The term «agent»

represent whomever a target identifies as being responsible for designing and

constructing a persuasion attempt (e.g., the company responsible for an

advertising campaign; an individual salesperson). Persuasion attempt

describes the target's perception of an agent's strategic behavior in

presenting information designed to influence someone's beliefs, attitudes,

decisions, or actions (e.g., ad, sales presentation, or message). Persuasion

episode implies a directly observable part of persuasion attempt, from

consumers’ point of view. For instance, if a consumer, when confronted with a

particular advertising message, treats it as a company's attempt to persuade

the consumer to buy the advertised product, the contact with an advertising

message, per se, is regarded as a persuasion episode impacts and consumer

thoughts about the nature, motives, and causes of persuasion tactics are

perceived persuasion attempt. When the target recognizes persuasion attempt, he

tries to cope with it. Coping can be in form of maintaining control over

the outcome or more active resistance to a persuasion attempt.the consumer

recognizes persuasion attempt or not, depends on consumer knowledge about an

agent, topic, and persuasion, per se. Agent knowledge may be information

regarding manufactures’ credibility [Artz, Tybout, 1999]; topic

knowledge may be information about brands [Wei, Fischer, Main, 2008] or

issues raised in the message (e.g. environmental issues) [Xie, Kronrod, 2012].

The authors pay special attention to persuasion knowledge which is «a

set of interrelated beliefs about (a) the psychological events that are

instrumental to persuasion, (b) the causes and effects of those events, (c) the

importance of the events, (d) the extent to which people can control their

psychological responses, (e) the temporal course of the persuasion process, and

(f) the effectiveness and appropriateness of particular persuasion tactics»

[Friestad, Wright, 1994]. The following elements (aspects) of persuasion

knowledge are worth being highlighted:

· Recognition of

persuasion attempt implies beliefs related to a mere

acknowledgement that the marketing stimulus is used as a persuasion tool;

· Inferences of

persuasion motives are beliefs about the possible end goals of

marketer;

· Beliefs about

the effectiveness of marketing tactics relate to how much the

marketing stimulus may affect his mental processes and behavior;

· Beliefs about

the appropriateness of marketing tactics are based on the comparison

of the marketing tactics with the «rules of the game», including notions of

fairness which are typically built into the culture, meaning they are shared by

many members of the socio-cultural environment in which the consumer lives.

Persuasion knowledge is an important construct

for consumers, because almost every interaction with marketing stimulus can be

regarded as a persuasion episode, in which the company is trying to convince

consumers that the product possesses some qualities, that the company is

socially responsible, etc. and, thus, influence consumers’ behavior (for

example, to persuade consumers to purchase the product). At the moment of

interaction with a specific marketing stimulus consumer may use his accumulated

knowledge to interpret the marketing stimulus and form an appropriate response

to it.differ in the volume and content of persuasion knowledge (between-subject

differentiation), which partly explains the differences in the interpretations,

and consequently, in the reactions of different consumers to the same marketing

stimulus. Furthermore, persuasion knowledge is a dynamic structure that may

change over time due to various factors, so the consumer may have different

volume and content of persuasion knowledge (within-subject differentiation) at

different times, and interprets and responds to the same marketing stimulus

differently.illustrate how consumer knowledge can influence the perception of a

marketing stimulus, we refer to the study of Kasherski and Kim [2010], who

examined consumer perceptions of different price presentation. They asked

respondents «Why do you think some retailers indicate the price taking into

account the cost of delivery (inclusive prices), while others indicate the cost

of delivery separately (partitioned prices)?». Some respondents interpreted

inclusive prices as a deliberate concealment of price structure that prevents

the correct assessment of the price, and preferred partitioned price

presentation; others perceived partitioned prices as a format that makes the

consumer focus on the base price of the product and leads to an underestimation

of the total costs, and preferred inclusive prices. Differences in

interpretations suggest that different consumers have different views how

different pricing tactics affect them and why firms use some tactics, which is,

inter alia, due to differences in persuasion knowledge.response to a marketing

stimulus depend on whether the consumer perceives it as a deliberate persuasion

attempt. Recognition of persuasion attempt entails a change in the consumer

reaction to a given stimulus («change of meaning» [Friestad, Wright, 1994]). To

demonstrate this principle, we can refer to research on children perceptions of

advertising. For example, Robertson and Rossiter [1974] found that when

watching television commercials children can identify two types of advertising

intents: informational («commercials are designed to transmit facts and

information») and persuasive («commercials are designed to affect consumer

attitude to the product or consumer buying behavior»). It was found that with

age children more often prescribe to the advertising persuasive intents as

opposed to informational intents, thus changing the interpretation of the

commercial over time. Along with the change of meaning there are changes in

children’s reaction to commercials: reduced confidence and deteriorating

attitude towards commercials, decreased motivation to buy the advertised

product, etc.knowledge is not the only factor that influences consumer

interpretation of marketing stimuli. Figure 2 is a diagram integrating the

antecedents and consequences of consumer persuasion knowledge activation,

which, in the author’s opinion, provides a comprehensive understanding of the

role of persuasion knowledge activation in the consumer response to marketing

stimuli. In more detail the model elements will be reviewed in the following

paragraphs.

Figure 2. Antecedents and Consequences of

Persuasion Knowledge Activation

Persuasion Knowledge: Terminological Analysis

Understanding the role of persuasion knowledge

activation in consumer response to marketing stimuli is impossible without a

clear understanding of distinctions and relations between the terms

«accumulated persuasion knowledge» and «situationally activated persuasion

knowledge» as well as their elements. Heretofore, accumulated persuasion

knowledge is considered as consumer persuasion-related beliefs which the

consumer has at a specific point in time and which have been accumulated on the

basis of previous marketplace experiences or external information, and

situationally activated persuasion knowledge is beliefs activated at the moment

of exposure to a marketing stimulus [Campbell, Kirmani, 2008] (see Figure

2).exposed to a marketing stimulus, consumers may activate thoughts about the

persuasion nature of a stimulus (How does the marketer persuade me?), about the

firm’s motives (Why does the marketer try to persuade me?), about the

effectiveness and appropriateness of persuasion attempts (To what extent is a

persuasion attempt effective and appropriate?). Undoubtedly, the distinction

between the above mentioned elements is conditional and is undertaken in order

to facilitate understanding of the possible directions of consumers’ thoughts.have

shown that the more persuasion knowledge and expertise consumers possess, the

more likely they recognize marketing tactics as persuasion attempts [Verlegh et

al., 2013]. However, it is not universal. For instance, even when consumers

know that firms can exaggerate the positive properties of the product in

advertising to influence the consumer's opinion, they can fail to recognize the

persuasion attempt at the moment of exposure to a particular advertisement and

believe the advertising information on the properties of the product under the

influence of other factors.and developing the ideas set out in the PKM, the

researchers operate with a variety of terms, which are to some extent related

to the concept of persuasion knowledge. An attempt to systematize the

terminology used in the literature is undertaken in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of the Terms Related to

Persuasion Knowledge

|

Term

|

Source

|

Definition

|

Elements of persuasion

knowledge

|

Nature of the construct

|

|

|

|

Awareness of persuasion

tactics

|

Inferred motives

|

Effectiveness judgments

|

Fairness judgments

|

Accumulated

|

Situationally activated

|

|

Suspicion

|

[Fein 1996; Ferguson,

et al., 2011]

|

Psychological state

when a consumer assumes that an agent might have some hidden motive.

|

+

|

+

|

|

|

+

|

+

|

|

Advertising skepticism

|

[Obermiller, Spangenberg, 1998]

|

General tendency to

distrust advertising messages.

|

+

|

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

Situational skepticism

|

[Foreh, Grier, 2003]

|

Situational state of

distrust to others and their motives.

|

+

|

+

|

|

|

|

+

|

|

Dispositional

skepticism

|

[Foreh, Grier, 2003]

|

General tendency to

distrust others.

|

+

|

+

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

Sentiment toward

marketing

|

[Gaski and Etzel, 1986]

|

General tendency to

think that firms are customer-oriented or not.

|

+

|

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

Inferred sincerity of

the motives

|

[Yoon, Gürhan-Canli, Schwarz, 2006]

|

Judgements related to

how agent’s stated motives correspond to real motives.

|

|

+

|

|

|

|

+

|

|

Inferences of hidden

motives

|

[Campbell, Kirmani,

2000]

|

Judgements about the

presence of agent’s hidden egoistic motives.

|

|

+

|

|

|

|

+

|

|

Prior knowledge about

agents’ motives

|

[Verlegh et al., 2013]

|

Consumer knowledge

about agents’ motives that has been accumulated prior to a particular episode

of consumer-agent interaction.

|

|

+

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

Perceived effectiveness

|

[Xie, Johnson, 2015]

|

Consumer judgements

related to how a tactic might influence himself and others.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

|

|

Perceived harm

|

[Xie, Madrigal, Boush,

2015]

|

Expected severity of

negative consequences cause by a marketing tactics.

|

|

|

+

|

+

|

|

+

|

|

Inferences of

manipulative intent

|

[Campbell, 1995]

|

Consumer judgements

that an agent might have an intent to persuade or influence consumer in an

inappropriate and manipulative manner.

|

|

+

|

|

+

|

|

+

|

|

Perceived deception

|

[Xie, Madrigal, Boush,

2015]

|

An extent to which a

marketing tactic is perceived as deceptive or misleading.

|

|

|

|

+

|

|

+

|

|

Perceived procedural

fairness

|

[Kukar-Kinney, Xia, Monroe, 2007]

|

Consumer judgements

related to the correspondence of marketing tactics, procedures, and processes

to the existing norms and rules.

|

|

|

|

+

|

+

|

+

|

|

Subjective persuasion

knowledge

|

[Bearden et al., 2001]

|

Subjective consumers’

evaluation of their knowledge of marketing tactics.

|

+

|

+

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

Pricing tactics

persuasion knowledge

|

[Hardesty et al., 2007]

|

Consumer knowledge of

different pricing tactics used in the marketplace, their influence

mechanisms, and agents’ intents behind their usage.

|

+

|

+

|

|

|

+

|

|

Terminological analysis revealed a significant

number of terms used by researchers to describe consumers' perceptions of

persuasion attempts. This terminological diversity can be explained with, at

least, several reasons:

a) The use of different terms to describe

similar concepts in different contexts

Inter alia, differences in terminology occur due

to the existence of different research traditions. For example, researchers in

the field of advertising used the construct «skepticism» long before the PKM

[Nelson, 1975]. Researchers in the field of pricing have traditionally used the

construct «fairness» to describe consumer judgments about the appropriateness

of price setting procedures, price presentations, and established price levels

[Campbell, 1999]. The later constructs «inferences of manipulative intent» and

«perceived deception» are conceptually similar constructs used in another

context.

b) The use of different terms to describe

different aspects of the phenomenon

Researchers used a variety of ways to categorize

consumer inferences of firms’ motives. In particular, in the studies there have

been used such dichotomous categories as «private vs public interests» [Foreh,

Grier, 2003], «increase profits vs compensate of costs of production»

[Campbell, 1999], and others., researchers of skepticism revealed a variety of

aspects of the phenomenon: situational skepticism, suggesting the presence of

the consumer of certain feelings or thoughts at some point of time, and

dispositional skepticism associated with the general consumer attitudes to the

world [Foreh, Grier, 2003].

c) The use of different operationalization

approaches

Using different operationalization approaches is

not a problem, per se. The difficulties arise when measurement scales relate to

incommensurate concepts that are masked by a single term. For example,

persuasion knowledge in the studies of Bearden et al. [2001] and Hardesty et

al. [2007] is defined similarly, but operationalized using different scales

which essentially measure the two different types of persuasion knowledge -

subjective («what consumers think they knows») and objective («what consumers

really know»).use of different terms to describe similar concepts, due to

differences in the historical trajectory of scientific fields, or the desire to

highlight a particular aspect of the phenomenon does not bring to

complications, provided that there is a clear understanding of the

relationships between these concepts. Despite that, researchers have repeatedly

argued for a more «economical» attitude towards the usage of terminology to avoid

the theoretical and empirical contradictions caused by terminological

negligence [Campbell, Kirmani, 2008].

Antecedents of Persuasion Knowledge Activation

It is important to note that the accumulated

consumer persuasion knowledge cannot always result in activation of

persuasion-related inferences in a particular situation. The differences in the

ability of consumers to activate persuasion knowledge can be due to a variety

of factors, including:

a) Individual characteristics

Among the characteristics that have an impact on

the ability to recognize persuasive nature of marketing stimuli, the age and

field of consumer professional activities have been identified [Boush,

Friestad, and Rose 1994; Friestad and Wright 1995]. Kirmani and Zhu [2007]

examined the role of regulatory focus (regulatory focus characterizes the

individual's strategy for achieving their goals) and came to the conclusion

that consumers focused on achieving positive results are more likely to realize

the persuasive nature of marketing stimuli than consumers focused on minimizing

negative results.

b) Marketing stimulus characteristics

Some marketing incentives are more likely to be

perceived as persuasion attempts. For example, commercials, wherein the

disclosure of the advertised brand occurs only at the end with the purpose to

attract consumer attention by creating a sense of suspense, are perceived by

consumers as more manipulative than traditional commercials, where disclosure

of the brand comes in the beginning [Campbell, 1995]. Partitioned prices that

have already been mentioned in the article are more often perceived by

consumers as «created with the intention to convince and influence» than

inclusive prices [Kachersky, Kim, 2010].

c) Situational characteristics

For example, Campbell and Kirmani [2000] have

shown that persuasion knowledge activation depends on whether the individual

acts as a direct recipient or the observer of persuasion episode. The cognitive

intensity of the situations differs. The recipient usually spends more

cognitive resources to solve problems arisen within the episode than an

observer. Thus, the recipient will have fewer cognitive resources to spend on

persuasion-related inferences than the observer, so the observer is more

inclined to recognize persuasion attempts than a direct participant in the

episode of exposure.

Consequences of Persuasion Knowledge Activation

In the existing literature there is a significant

number of attempts undertaken to investigate the response of consumers to

various marketing stimuli in a situation of persuasion knowledge activation.

Research of the consequences of persuasion knowledge activation covers a wide

range of marketing tools used in various fields of marketing practices. Despite

the diversity of marketing stimulus, consumer response is exhibited in a

limited number of «coping tactics»:

) Critical assessment of the product offering,

counterargument and counterbehavior (the formation of attitudes and behaviors

that are contrary to those instigated in the marketing stimulus);

) Less favorable assessment of the marketing

stimulus (in comparison with a situation where the consumer does not recognize

persuasive nature of marketing stimulus);

) Less favorable assessment of the product;

) Weakening of consumer intentions and behaviors

in relation to the product;

) Less favorable assessment of the company

initiating marketing tactics;

) Less favorable assessment of related subjects

(e.g. the sponsored event; distributor’s products);

) Supportiveness of the legal regulation of

marketing activities.of the above stated coping responses are given in Table 2.

Table 2. The Effect of Persuasion Knowledge

Activation on Consumer Response to Marketing Stimulus

|

Marketing area

|

Marketing stimulus

|

Source

|

Main findings

|

Type of response*

|

|

Advertising

|

Comparative advertising

|

[Jewell, Barone, 2007]

|

Within-category

comparisons were perceived as a more appropriate tactic and were thus more

effective in positioning the focal brand than were between-category

comparisons.

|

2, 3

|

|

Guilt appeals

|

[Hibbert et al., 2007;

Cotte et al., 2005]

|

Guilt arousal is positively

related to donation intention, and that persuasion and agent knowledge impact

the extent of guilt aroused. Manipulative intent and the respondents'

skepticism toward advertising tactics in general are negatively related to

guilt arousal but that their affective evaluation and beliefs about a charity

are positively related to feelings of guilt. However, there is a positive

direct relationship between perceived manipulative intent and the intention

to donate.

|

1, 2, 4, 5

|

|

Brand placement

|

[Wei et al., 2008]

|

Persuasion knowledge

activation can negatively affect consumer evaluations of embedded brands;

however, negative effects are qualified by perceived appropriateness of

covert marketing tactics and by brand familiarity. Further evidence indicates

a condition under which activation can actually have a positive effect on

consumer evaluations.

|

2, 5, 6

|

|

Advertising frequency

|

[Campbell, Keller,

2003]

|

Negative thoughts about

tactic inappropriateness were seen to arise with repetition, particularly for

an ad for an unfamiliar brand, driving, in part, the decreases in repetition

effectiveness.

|

2, 3

|

|

Pricing

|

Price increase

|

[Campbell, 1999]

|

When participants

inferred that the firm had a negative motive for a price increase, the

increase was perceived as significantly less fair than the same increase when

participants inferred that the firm had a positive motive. Perceived

unfairness leads to lower shopping intentions.

|

2, 4

|

|

Tensile price claims

|

[Hardesty et al., 2007]

|

Individuals with higher

levels of pricing tactic persuasion knowledge (PTPK) were shown to have more

knowledge-related thoughts regarding pricing tactic information and exhibited

more purchase interest following exposure to tensile claim offers than those with

low levels of PTPK.

|

4

|

|

Baseline omission

|

[Xie, Johnson, 2015]

|

Consumers tend to

perceive baseline omission as more effective on others than on themselves.

The self-others difference is more salient among consumers with more

persuasion knowledge. Consumers’ concerns about its effectiveness on

themselves, rather than on others, better predict their supportiveness to

regulate the use of baseline omission.

|

7

|

|

Interpersonal selling

|

Asking intention

questions

|

[Williams et al., 2004]

|

When persuasive intent

is attributed to an intention question, consumers adjust their behavior as

long as they have sufficient cognitive capacity to permit conscious

correction. When respondents are educated that an intention question is a

persuasive attempt, the behavioral impact of those questions is attenuated.

|

1

|

|

Public Relations

|

Sponsorship

|

[Foreh, Grier, 2003]

|

Consumer evaluation of

the sponsoring firm was lowest in conditions when firm-serving benefits were

salient and the firm outwardly stated purely public-serving motives. The

potential negative effects of skepticism were the most pronounced when

individuals engaged in causal attribution prior to company evaluation.

|

5

|

|

Video news releases

|

[Nelson, Park, 2015]

|

Viewers’ beliefs about

and perceptions of credibility in a news story are altered when they acquire

persuasion knowledge about VNRs and learn that the source of the story was an

unedited VNR.

|

2

|

|

Branding

|

Brand imitation

|

[Van Horen, Pieters,

2012]

|

Consumers consider

feature imitation to be unacceptable and unfair, which causes reactance

toward the copycat brand. Yet, even though consumers are aware of the use of

theme imitation, it is perceived to be more acceptable and less unfair, which

helps copycat evaluation.

|

2, 3

|

|

Brand names and slogans

|

[Laran et al., 2011]

|

Brands cause priming

effects (i.e., behavioral effects consistent with those implied by the

brand), whereas slogans cause reverse priming effects (i.e., behavioral

effects opposite to those implied by the slogan). For instance, exposure to

the retailer brand name «Walmart,» typically associated with saving money,

reduces subsequent spending, whereas exposure to the Walmart slogan, «Save

money. Live better,» increases it.

|

1

|

|

Product policy

|

Versioning

|

[Gershoff, Kivetz,

Keinan, 2012]

|

The production method

of versioning may be perceived as unfair and unethical and lead to decreased

purchase intentions for the brand.

|

2, 4

|

|

Default options

|

[Brown, Krishna, 2004]

|

A default option can

invoke a consumer's «marketplace metacognition,» his/her social intelligence

about marketplace behavior that leads to different predictions than accounts

based on cognitive limitations or endowment: in particular, it predicts the

possibility of negative or «backfire» default effects.

|

1

|

|

Retailing

|

Atmosphere of the

retail store

|

[Lunardo, Mbengue, 2013]

|

Incongruent store

environments urge consumers to make inferences of manipulative intent from

the retailers, and that those inferences negatively influence consumer's

perception of the retailers' integrity, and attitudes toward the atmosphere

and the retailers.

|

5

|

*The number in the row corresponds to the

following coping tactics: [1] Critical assessment of the product offering,

counterargument and counterbehavior; [2] Less favorable assessment of the

marketing stimulus; [3] Less favorable assessment of the product; [4] Weakening

of consumer intentions and behaviors in relation to the product; [5] Less

favorable assessment of the company initiating marketing tactics; [6] Less

favorable assessment of related subjects; [7] Supportiveness of the legal

regulation of marketing activities.Correction of judgment and behavior usually

occurs in a direction opposite to that intended with marketing stimulus.

Instead of the expected favorable attitude to the product and higher purchase

likelihood, when consumers perceive marketing stimulus as a persuasion attempt,

they tend to react in the opposite way: less favorable attitude toward the

product, the manufacturer, as well as intermediaries involved in the process.

This, as a result, reduces purchase likelihood and accelerates switching to

competitive offerings. Moreover, the lack of trust between the consumer and the

firm can lead to resistance to buy not only a particular product, but all

products related to the firm [Reichheld, Schefter, 2000]. However, it is worth

noting that despite the dominant number of adverse consequences for businesses

resulting from persuasion knowledge activation, there is a precedent when

persuasion knowledge activation had a positive impact on the assessment of the

brand [Wei et al., 2008].above examples demonstrate the importance of consumer

perceptions of marketing stimulus for consumers themselves, companies that

initiate marketing activities, and intermediaries that implement marketing

activities (e.g., distributors and media agencies). Let us consider in more

detail the possible outcomes of firm-consumer interactions when persuasion

knowledge is activated and inhibited (see Figure 3).

3. Matrix of

Firm-Consumer Interaction Outcomes

3. Matrix of

Firm-Consumer Interaction Outcomes

equivalent interaction can take place when

neither the company intends to persuade the consumer, nor the consumer

mistakenly attributes persuasion intent to marketing stimuli. However, this

situation is very unlikely in the context of modern highly competitive

environment wherein marketers use a wide arsenal of marketing tools to attract

attention and retain customers. An equivalent interaction also occurs when a

firm intention fully understood by the consumer and the firm correctly

evaluates consumer persuasion knowledge that may affect its response to the

tactics used. When a company has no information about consumer persuasion

knowledge, it is in a vulnerable position, since the expected efficiency of the

marketing stimulus may differ from the real effect produced by the use of the

stimulus. That point highlights the importance for companies to study consumers

under a new angle: not only consumers’ perceptions of companies and products

are important, but also their perceptions of marketing tools used by companies.

If the firm lacks understanding of this aspect, it could lead to a kind of

«marketing myopia» [Levitt, 1960].situation when the consumer is not aware of

persuasion intent, as a rule, leads to an unfavorable outcome for the consumer

(e.g., psychological dissatisfaction or financial losses). It can occur when

the consumer has insufficient amount of knowledge and experience. Such a

situation may arise in the case of immature consumers (children and

adolescents) [Robertson et al., 1974], consumers in the new or emerging market,

who have not yet developed immunity to the marketing tactics of influence used

by companies and are easily influenced by marketing tools [Feick, Gierl, 1996;

La Ferle, Kuber, Edwards, 2013].is worth noting that despite persuasion

knowledge allows consumers to use the arsenal of coping tactics in response to

marketing persuasion attempts, it may not always be properly activated. As

previously mentioned, the consumer may attribute to the firms’ actions ulterior

motives even in the absence of such intentions on the side of the firm [Koslow,

2000]. The reasons for such an outcome may be a false attribution of the

recipient caused by excessive skepticism about marketing in general, about

certain marketing tools, such as advertising, about certain products or firms.

This situation, of course, is problematic for the company, because it reduces

the effectiveness of a marketing stimulus. It can also lead to consumers’

disadvantages, because it distorts objective information and prevents consumers

from selecting the best alternative.persuasion knowledge plays an important

role in the consumer response to various marketing stimuli. A review of the

empirical studies has shown that, when consumers interpret marketing stimuli as

persuasion attempts, firstly, they evaluate these marketing stimuli more

critically and, secondly, modify their judgements and behavior with respect to

marketing stimuli, related products and firms. Generally, this leads to adverse

consequences for firms. However, it is not justified to claim that persuasion

knowledge activation always results in unfavorable outcomes for companies. For

instance, when consumers perceive persuasion attempt as «fair» or

«appropriate», they cannot modify their behavior. Different persuasion-related

beliefs as well as its antecedent and consequences are discussed in the

article.the persuasion knowledge has a significant effect of consumer response

to marketing stimuli, it is reasonable for firms to include it in the list of

permanently tracked consumer characteristics. Together with economic,

demographic and other characteristics of consumers, persuasion knowledge can be

regarded as a basis for consumer segmentation, so that firms can tailor

marketing stimuli to each group of consumers. In addition to taking persuasion

knowledge as given, firms can take an active part in their formation and

management with the help of marketing communications and consumer education.the

variety of empirical studies on persuasion knowledge, the conceptual core of

the phenomenon remained unchanged and almost did not get a theoretical

extension since the introduction of the concept into scientific discourse in

1994. Furthermore, some empirical studies have generated conflicting results,

which provides fertile grounds for further researching and strengthening the

theoretical foundations of persuasion knowledge. It seems promising to further

test the relationship between accumulated and situationally activated

persuasion knowledge, which has been done only once so far in [Verlegh et al.,

2013]. It is also worth examining how persuasion knowledge change over time. The

need to include into the economic theory some factors that take into account

the ability of economic agents to learn their surroundings and change their

economic behavior based on acquired information has been announced long before

the PKM [Simon, 1959]. In the PKM it becomes even more appealing to undertake

longitudinal studies that trace consumer persuasion knowledge over time,

because consumers are not «in a vacuum»: they constantly update their knowledge

and, in turn, alter the reaction to a marketing stimulus. Thus, the consumer

reaction to the same marketing incentive may be different at different times,

which certainly should be considered marketing practices in the planning and

implementation of marketing activities aimed at consumers.

2. Исследование роли осознания потребителем

воздействия со стороны фирмы в формировании реакции на уменьшение размера

продукта

.1 Уменьшение размера продукта как ценовая

тактика

По материалам статьи «Цена и размер продукта как

альтернативные инструменты влияния на поведение потребителей на рынке товаров

повседневного спроса». Маркетинг и маркетинговые исследования 6 (2014):

424-432.

Растущая конкуренция на многих рынках товаров и услуг

заставляет компании постоянно искать новые способы привлечения внимания и интереса

потребителей. Сохранение и упрочнение рыночных позиций невозможно без понимания

поведенческих реакций потребителей на принимаемые фирмой маркетинговые решения.

Превращение потребителя в центральную фигуру на высококонкурентных рынках

подчеркивает важность изучения поведения потребителей с точки зрения

потребности бизнеса и необходимость выявления новых паттернов их поведения,

способных повлиять на деятельность компании.

Несмотря на долгую традицию изучения потребительского

поведения, актуальность данной области исследований продолжает оставаться

высокой. Ограниченность экономического подхода, преобладавшего на более раннем

этапе развития науки о потребителе и потреблении, способствует обращению

интереса современных ученых к междисциплинарным исследованиям, опирающимся на

социологические, психологические и антропологические методы. Использование

междисциплинарного подхода дает возможность комплексно посмотреть на поведение

потребителя, позволяя конструировать модели потребительского поведения,

наиболее точно и подробно описывающие реальную картину.

В данной работе исследуется вопрос влияния на потребителя

таких маркетинговых инструментов, как цена и размер продукта. На основании

обзора существующих работ по данному вопросу определяется степень разработанности

проблемы, и выявляются малоизученные направления исследований, которые являются

перспективными как с теоретической, так и с практической точек зрения.

Покупательское поведение потребителей на рынке товаров

повседневного спроса

Под покупательским поведением потребителей, как правило,

понимается совокупность психологических процессов и физических действий

отдельных лиц или групп лиц, которые имеют место при осуществлении ими покупки

товаров и услуг с целью конечного потребления [3].

Согласно определению покупательское поведение потребителей

можно условно разделить на психологическую (когнитивную / аффективную) и

поведенческую компоненты. Психологическая компонента может выражаться в

отношении к продукту/ бренду/ производителю, суждениях о качестве продукта и

др., а поведенческая компонента, связанная с действиями потребителя в отношении

продукта - в намерении покупателя совершить покупку, готовности платить за

продукт определенную цену, выбор продукта из ряда альтернатив и др.

Процесс покупки товаров повседневного спроса часто

характеризуется низкой степенью вовлеченности. В результате чего потребители не

производят глубокого поиска и анализа информации о продукте, а полагаются на

такие внешние индикаторы, как цена продукта, упаковка продукта (в том числе ей размер),

страна-производитель, известность бренда продукта и др.

Влияние цены и размера продукта на поведение потребителей:

текущее состояние вопроса

Цена как объект изучения экономической науки имеет длинную

историю. В микроэкономике цена продукта является основополагающим фактором,

определяющим потребительский спрос на продукт, наряду с доходом потребителя

ценами на конкурентные товары (товары-заменители). Раздел микроэкономики, в

котором изучается вопрос о том, какой товар или набор товаров выбирает потребитель

при заданных ограничениях, называется теорией потребительского выбора и спроса.

Согласно закону спроса, для большинства товаров между ценой и

спросом на продукт существует обратная зависимость: снижение цены провоцирует

за собой увеличение спроса на продукт при прочих равных условиях. Для того

чтобы измерить реакцию покупательского спроса к изменению цены используется

коэффициент эластичности спроса, который определяется как процентное изменение

количества спроса, деленное на процентное изменение цены.

Подход к влиянию изменения цены на поведение потребителя,

используемый в маркетинге, несмотря на схожесть по ключевым вопросам, несколько

отличается от микроэкономического подхода, в том числе своей терминологической

базой. Так, спрос на продукт обусловлен восприятием потребителями ценности

продукта, которая в свою очередь зависит от соотношения воспринимаемых выгод

(размер продукта, качество продукта и др.) и воспринимаемых затрат на

приобретение продукта (цена, время, потраченное на приобретение и др.) [16].

Продукты, обладающие более высокой воспринимаемой ценностью для потребителя,

как правило, пользуются большим потребительским спросом: из двух одинаковых по

своим характеристикам и предоставляемым выгодам альтернатив потребитель

предпочтет тот, цена на который ниже.

Производя оценку изменения цены, потребитель не просто

количественно измеряет изменение своих выгод, но и делает суждения относительно

того, было ли данное изменение справедливым или несправедливым, существенным

или несущественным, большим или маленьким, что в конечном итоге также оказывает

влияние на спрос на данный продукт [1].

Также в маркетинге появляется понятие референтной цены -

цены, на которую потребитель ориентируется и с которой сравнивает цену

интересующего его товара. При этом базой для формирования референтной цены

может служить не только уровень цен на рынке и цены аналогичных товаров, но и

внутренние субъективные представления потребителя о цене, предшествующий опыт

приобретения продукта [9].

В отличие от цены, проблема влияния изменения размера

продукта на покупательское поведение потребителей не получила широкого

распространения в научной литературе. Но востребованность данного инструмента

является высокой: компании прибегают как к увеличению (product supersizing), так и к сокращению

размера единицы продукта (product downsizing).

Поскольку от размера продукта (при прочих равных условиях) во

многом зависят выгоды, которые получит потребитель от покупки, размер продукта

и уровень спроса на продукт для большинства продуктов связаны прямой

зависимостью.

Существует ряд работ, в которых производится сравнительное

исследование чувствительности покупательского спроса к эквивалентным изменениям

цены и размера продукта. Результаты некоторых исследований представлены в

Таблице 1.

Таблица 1. Сравнение чувствительности потребительского спроса

к изменению цены и размера продукта

|

Исследование

|

Характер изменения ценности продукта

|

Метод исследования

|

Категория продуктов

|

Модераторы

|

Результаты

|

|

[Hardesty, Bearden, 2003]

|

Увеличение

|

Лабораторный эксперимент

|

Зубная паста Мыло

|

Размер предоставляемой выгоды 1) Высокий 2)

Умеренный и невысокий

|

E(price) > E(size) E(price) = E(size)

|

|

[Mishra, Mishra, 2011]

|

Увеличение

|

Лабораторный

эксперимент

|

Черничные маффины с низким содержанием жиров

(как относительно полезный для здоровья продукт) и шоколадное печенье (как

вредный для здоровья продукт), реализуемые в кофейнях Starbucks

|

Полезность продукта для здоровья: 1)

Полезные для здоровья продукты 2) Вредные для здоровья продукты

|

E(price) <

E(size) E(price) > E(size)

|

|

[Gourville, Koehler, 2004]

|

Уменьшение

|

Лабораторный эксперимент Панельные

сканнер-данные

|

Кофе Готовые обеды

|

-

|

E(price) > E(size)

|

|

[Cakir, Balagtas, 2013]

|

Уменьшение

|

Панельные сканнер-данные

|

Мороженое

|

-

|

E(price) > E(size)

|

|

[Imai, Watanabe, 2014]

|

Уменьшение

|

Панельные сканнер-данные

|

Различные категории товаров потребительского

спроса

|

-

|

E(price) = E(size)

|

Хардести и Берден [6] осуществили серию лабораторных

экспериментов с товарами повседневного спроса. В одном из экспериментов авторы

исследуют эффективность различных форматов промо-акций на примере тюбика зубной

пасты размером 5,2 унций, который изначально предлагался по цене $2,59 (или

$0,5 за унцию). Они сравнивают реакцию потребителей на ценовую скидку в размере

10 %, 25 % и 50 % от прежней цены с предложением 10 %, 25 % и 50 % бонусного

количества зубной пасты соответственно по прежней цене. По результатам

эксперимента потребители оказались одинаково чувствительны к ценовой скидке и

бонусному продукту в размерах 10 % и 25 %, однако при предложении 50 % скидки

от прежней цены и 50 % бонусного продукта по прежней цене потребители отдали

предпочтение первому варианту. Авторы заключают, что в условиях, когда размер

предоставляемой выгоды высок, потребитель более чувствителен к уменьшению цены,

чем увеличению количества продукта; когда же размер получаемой выгоды

воспринимается как невысокий или умеренный, потребитель одинаково чувствителен

и к изменению цены, и к изменению количества продукта. Стоит отметить, что с

точки зрения экономики 50 % скидка от прежней цены за упаковку продукта и 50 %

бонусного продукта по прежней цене не являются эквивалентными предложениями,

так как в первом случае цена за 1 унцию продукта составляет $0,25, а во втором

- $0.33. В связи с этим, предпочтение потребителем скидки в размере 50 %

увеличению размера продукта на 50 % при прежней цене является экономически

рациональным выбором. Однако расчет коэффициентов ценовой эластичности спроса

позволяет более точно и глубоко проанализировать реакцию потребителей на

соответствующие предложения и выявить паттерны поведения, отклоняющиеся от

общепринятых в классической экономической теории взглядов. Пример расчета

коэффициентов на основании данных, полученных в исследовании Хардести и

Бердена, приведен в Таблице 2.

Таблица 2. Расчет коэффициентов ценовой эластичности спроса

при изменении номинальной цены за упаковку продукта и размера продукта

|

Формат промо-акции

|

Наименование показателя

|

Размер скидки/ бонуса

|

|

|

10 %

|

25 %

|

25 %

|

50 %

|

|

Ценовая скидка

|

Стоимость одной унции продукта

|

0.45

|

0.37

|

0.37

|

0.25

|

|

Уровень спроса

|

15.34

|

18.33

|

18.33

|

23.05

|

|

E(price)

|

-1.10

|

-0.79

|

|

Бонусный продукт

|

Стоимость одной унции продукта

|

0.45

|

0.40

|

0.40

|

0.33

|

|

Уровень спроса

|

16.05

|

18.00

|

18.00

|

20.37

|

|

E(size)

|

-1.09

|

-0.75

|

Важно подчеркнуть, что при расчете ценовой эластичности

спроса используется цена за универсальную меру продукта (грамм, миллилитр,

унция и др.), а не номинальная цена за упаковку продукта, поскольку именно цена

за универсальную единицу отражает реальную стоимость продукта. Как можно

увидеть в Таблице 2, абсолютное значение эластичности потребительского спроса

при одинаковых изменениях цены за унцию, когда изменение представлено в виде 50

% ценовой скидки, больше, чем когда оно представлено в виде предложения 50 %

дополнительного продукта (|-0.79| > |-0.75|); когда же размер скидки меньше

и равен 25 %, то значения ценовой эластичности при изменении номинальной цены

за упаковку продукта и размера продукта практический равны (|-1.10| ≈

|-1.09|).

Коэффициенты ценовой эластичности спроса при изменении

номинальной цены за упаковку продукта и размера упаковки продукта в последующих

исследованиях осуществляются аналогичным образом.

Мишра и Мишра [11], также проведя серию лабораторных

экспериментов, заключают, что потребители предпочитают бонусный продукт ценовым

скидкам для полезных для здоровья продуктов и обратное для вредных для здоровья

продуктов. Авторы связывают это с тем, что потребление дополнительного

количества вредного для здоровья продукта ассоциируется у потребителя с негативными

последствиями, в связи с чем воспринимаемая ценность подобного предложения

снижается, в то время как аналогичное предложение для полезного для здоровья

продукта воспринимается потребителем положительно.

Гурвилл и Кёлер [5] с помощью лабораторных экспериментов и

исследований на основании панельных сканнер-данных выявили, что потребители

более чувствительны к увеличению цены, чем уменьшению количества продукта.

Сакир и Балактас [4] с помощью модели дискретного выбора

оценили изменения спроса на продукт при изменении цены и размера продукта на

основе панельных данных, полученных с помощью сканера, об оптовых покупках

мороженого домохозяйствами в Чикаго. Главным выводом стало, что потребители

менее чувствительны к размеру пакета, чем к цене; эластичность спроса по

отношению к размеру пакета составляла примерно одну четвертую величины

эластичности спроса по отношению к цене.

Причины подобных различий в чувствительности потребительского

спроса могут заключаться в существовании визуальных искажений психофизического

восприятия и особенностях механизмов «ментального учета». В теории

предполагается, что потребители принимают рациональные и логические решения с

использованием всей имеющейся информации. Со временем количество информация о

продукте, содержащейся на упаковке продукта, значительно возросло. Несмотря на

это повышение доступности информации о продукте, исследования свидетельствует о

том, что лишь незначительная часть потребителей использует данную информацию,

принимая решение о выборе продукта [8]. В результате, потребители не принимают

во внимание уменьшение размера продукта и оказываются не в состоянии

максимизировать свои выгоды. При совершении покупки потребитель часто

полагается не на информацию о реальном количестве продукта, а на воспринимаемое

количество продукта, при этом восприятие количества продукта может быть

искажено под воздействием размера и формы продукта [15]. Учитывая то, что

компании не подвергают информацию об уменьшении количества продукта широкой

огласке, уменьшение количества продукта может остаться незамеченным

потребителем, если воспринимаемый размер продукта остался неизменным.

Имаи и Ватанабе [7], изучив данные о потребительских покупках

товаров повседневного спроса в 200 супермаркетах в Японии в 2000-2012 гг.,

пришли к заключению, что уменьшение размера продукта приводит к уменьшению

объемов потребления данного продукта. При этом, в отличие от указанных ранее

результатов, авторы утверждают, что чувствительность спроса к изменению размера

продукта в Японии в 2000-2012 гг. была практически такой же, как и

чувствительность к изменению цен.

Таким образом, исследования различий между чувствительностью

потребительского спроса к изменениям цены и размера продукта имеют

противоречивые результаты.

Цена и размер продукта как альтернативные маркетинговые

инструменты

В управленческой практике изменение размера продукта

представляет собой инструмент, альтернативный изменению цены продукта. В

частности, выбор одной из указанных альтернатив может иметь место при решении

следующих управленческих проблем:

· Повысить рентабельность продукта, подняв цену

продукта или уменьшив размер единицы продукта?

· Простимулировать спрос на продукт, временно

уменьшив стоимость продукта или увеличив размер единицы продукта?

На все более конкурентном и изменчивом рынке с большим

количеством товаров-заменителей, доступных практически для любого продукта

повседневного спроса, увеличение цены становится рискованной стратегией для

производителей и ритейлеров. Оказавшись в такой ситуации, где рост цен может

быть губительным для деятельности компании, компании часто прибегают к

модификации упаковки продукта и уменьшению содержимого упаковки при сохранении

его цены.

Мощным стимулом для компаний, чтобы сохранить цену на

нынешнем уровне могут послужить концепции референтной цены и ценового порога.

Хотя референтная цена может формироваться под воздействием различных факторов,

чрезвычайно важным фактором, определяющим ее, является цена, которую покупатель

запоминает от предыдущего приобретения конкретного продукта или продукта в категории

[12]. Ценовой порог, с другой стороны, представляет собой диапазон допустимых

цен на данный продукт [13]. Монро и Кокс [12] показывают, что покупатели при

походе по магазинам обычно используют референтную цену в качестве якоря, против

которого они оценивают цены на продукты. Для продуктов, которые могут быть

легко замещены и где потребители имеют относительно высокий уровень

осведомленности о ценах в категории, верхний ценовой порог на эти продукты, как

правило, довольно узкий. Учитывая это, увеличение цены продукта, чтобы улучшить

рентабельность, теряет свою привлекательность. Не имея альтернативы, кроме как

поддерживать статус-кво в области ценообразования, компании вынуждены идти на

сокращение размера единицы продукта, чтобы повысить рентабельность.

Таким образом, в целях повышения рентабельности продукта

многие компании могут повысить цену на свою продукцию или уменьшить размер

единицы производимой продукции, сохраняя цену продукции на прежнем уровне. Обе

эти практики могут восприниматься потребителем как сокращение воспринимаемой

ценности продукта и привести к переключению на другой продукт, в большей

степени отвечающий требованиям потребителя.

Принимая во внимание возможную негативную реакцию

потребителей, производители, как правило, не афишируют факт уменьшения размера

продукта. Однако данная практика довольно активно используется многими

компаниями в разных странах. По информации, размещенной на портале lenta.ru в

июле 2009 [2], «компания Mars уменьшила массу продаваемых в Великобритании шоколадных

батончиков «Марс» и «Сникерс» на 7 %. Представители компании признались, что

эта мера вызвана увеличившимися затратами на производство. Цена на шоколадные

батончики осталась прежней, при этом батончики стали весить 58 граммов вместо

прежних 62,5 граммов».

С точки зрения неоклассической микроэкономики потребители

одинаково реагируют на соизмеримые изменения цены и размера продукта. Однако

взгляд на данную проблему с позиции поведенческой экономики и маркетинга,

активно задействующих знания из психологии, отличается от утверждений, принятых

в неоклассической экономике. Подход, используемый в маркетинге и поведенческой

экономике, в отличие от неоклассической микроэкономики, носит позитивный

характер и позволяет более точно объяснить поведение экономических объектов,

максимально приблизив его к реальному поведению.

Опираясь на результаты эмпирических исследований, в которых

доказывается, что влияние соизмеримых изменений цены и размера единицы продукта

на потребителей различно, а именно потребители более чувствительны к изменению

цены при неизменном объеме продукта, чем к изменению количества продукта при

неизменной цене (см. Таблицу 1), можно предположить, что при необходимости

оптимизировать производственные издержки уменьшение размера продукта представляется

менее рискованной стратегией, поскольку уменьшение количества продукта в

меньшей степени отразиться на потребительском спросе, чем увеличение цены. В

случае же выбора метода стимулирования спроса, временное снижение цены приведет

к большему увеличению спроса, чем увеличение размера единицы продукта.

Несмотря на краткосрочные выгоды ценового стимулирования

спроса (больший прирост спроса за счет сокращения цены, чем увеличения размера

продукта), подобная стратегия имеет ряд негативных последствий для деятельности

компании в долгосрочной перспективе. В частности, частые ценовые скидки

увеличивают чувствительность потребителей к цене [12]. Это означает, что в

долгосрочной перспективе спрос на продукцию во время отсутствия ценовых скидок

может сокращаться до существенно более низкого уровня, чем тот, который

наблюдался при такой же цене до момента использования компанией стратегии

постоянного ценового стимулирования продукта. В подобных условиях производители

становятся «заложниками» созданной собственными силами ситуации: они вынуждены

постоянно предлагать скидки потребителям для того чтобы подержать продажи своей

продукции на планируемом уровне. Учитывая данные обстоятельства, использование

количественных способов стимулирования спроса представляется перспективной

альтернативой. Изучение влияния изменений размера продукта, предоставление

дополнительного количества продукта, при стимулировании спроса на продукт на

чувствительность спроса может открыть новые аспекты покупательского поведения

потребителей, предоставив компаниям дополнительные рычаги воздействия на

потребителей в высококонкурентной рыночной среде.

Также, частое снижение цен может вызывать у потребителя

ассоциации с низким качеством продукта, негативно сказываться на имидже бренда

и привести к падению капитала бренда (brand equity) [15]. Эмпирические

доказательства того, что увеличение размера продукта имеет подобные последствия

отсутствуют.

Перспективные направления исследований влияния

цены и размера продукта на поведение потребителей

Поскольку изменения цены и размера продукта могут

рассматриваться как альтернативные маркетинговые инструменты, представляется

актуальным более глубокое изучение и сравнение влияния данных инструментов на

покупательское поведение потребителей. Центральными в данных условиях

становятся следующие вопросы: Существуют ли различия в поведении потребителей

при соизмеримых изменениях цены и размера продукта на рынке товаров

повседневного спроса? Характерны ли данные различия для разных категорий

продуктов? Некоторые потенциальные направления исследований влияния изменений

цены и размера продукта на покупательское поведение потребителей представлены в

Таблице 3.

Таблица 3. Перспективные направления исследований влияния

цены и размера продукта на поведение потребителей

|

Аспекты поведения потребителей

|

|

Чувствительность потребительского спроса

|

Отношение к продукту

|

|

Маркетинговые задачи и методы их решения

|

· Сравнение чувствительности потребительского

спроса к снижению цены и соизмеримому увеличению размера продукта · Изучение влияния

периодического увеличения размера продукта на чувствительность спроса в

долгосрочной перспективе и сравнение данной реакции потребителя с реакций на

сопоставимые увеличения цены

|

· Изучение влияния периодического увеличения

размера продукта на отношение к продукту и сравнение данной реакции

потребителя с реакцией на сопоставимые снижения цены

|

|

Повышение рентабельности продукта: повышение

цены VS уменьшение размера продукта

|

· Сравнение чувствительности потребительского

спроса к повышению цены и уменьшению размера продукта

|

· Изучение влияния уменьшения размера продукта на

отношение потребителя к продукту и сравнение данной реакции потребителя с

реакций на сопоставимое увеличение цены

|

Существующие исследования, в которых производится сравнение

влияния соизмеримых изменений цены и размера продукта на поведение потребителей

фокусируются на изучении непосредственных действий потребителей, которые

выражаются в спросе на продукт. Результаты данных исследований имеют

противоречивые результаты и требуют дальнейшей более глубокой проработки. Кроме

того, феномен «поведение потребителей» не ограничивается лишь изучением

потребительского спроса, а включают в себя целый спектр различных элементов.

Изучение психологических аспектов поведения также представляется крайне

актуальным, поскольку во многом именно скрытые от прямого наблюдения

психологические процессы, происходящие в «черном ящике» сознания потребителей,

определяют их дальнейшие поступки.

Поведение потребителей представляет собой динамичный и

постоянно подвергающийся изменениям феномен. Вопрос влияния цены на поведение

потребителя уходит корнями в экономическую теорию, история которой насчитывает

не одно столетие, а также активно освещается в литературе по маркетингу. В то

же время размер продукта, как альтернативный цене маркетинговый инструмент,

практически не освещался ни в зарубежной, ни в российской научной литературе.

При этом, распространенность использования данного инструмента в маркетинговой

практике довольно широка: в целях повышения рентабельности продукта многие

компании сокращают размер продукта, оставляя цену на неизменной уровне, или

стимулируют спрос на продукт с помощью предложения дополнительного количества

продукта по неизменной цене.

Проведение эмпирических исследований, дающих более глубокое

понимание механизмов влияния изменений размера продукта на поведение

потребителей, даст компаниям более полное представление о последствиях

предпринимаемых ими действий и позволит точнее оценивать их результативность и

эффективность. Для теории маркетинга исследование данного вопроса также

представляется актуальным, поскольку оно позволяет более комплексно осветить

механизмы принятия потребителем решения о покупке и выявить аспекты поведения

потребителей, отклоняющиеся от предпосылок о рациональности потребителей,

принятых в неоклассической экономической теории.

2.2 Результаты эмпирического исследования роли

осознания потребителем воздействия со стороны фирмы в формировании реакции на

уменьшение размера продукта

По материалам научного доклада «Consumer

Response to Unit Price Increase: the Role of Pricing Tactics and Consumer

Knowledge». Working Paper # 14 (E) - 2015. Graduate School of Management, St.

Petersburg State University: SPb, 2015.

Introduction

Price increases are a widespread phenomenon in a

variety of markets. Such increases can be driven by market factors or by a

desire of the company to increase profit margins. Regardless of the purpose of

price increases, consumers usually negatively react to them as they has a

detrimental effect on their wellbeing. Under the unfavorable economic

circumstances, when consumer behavior is characterized by the accelerating

rationalization, economizing and the weakening of brand loyalty, the consumer

response to price increases can be extremely harsh. To mitigate the negative

consumer response to a price increase, companies can manage the way a price

increase is presented to the market. Instead of raising the price for a

product, the company can decrease the quantity/size of a product and remain the

price of the product item unchanged. On the one hand, it allows keeping the

product available for consumers; on the other hand, it makes hard to compare

prices directly, which could be potentially perceived by consumers as unfair or

deceptive (Zaltman, 1978; Hardesty, Bearden, Carlson, 2007).motivation of

marketers behind using pricing tactics that can mislead consumer from making an

optimal choice is the possibility to get additional benefits. Marketers may not

necessarily be trying to deceive consumers, but they are often affected

nonetheless (Manning et al. 1998; Sprott et al. 2003). When describing their

lives as consumers, people point out «the confusing, stressful, insensitive,

and manipulative marketplace in which they feel trapped and victimized»

(Fournier, Dobscha, Mick, 1998). Similarly McGraw and Tetlock (2005) reason:

«Consumers who have been gulled into thinking of themselves as part of a

corporate family or partnership may feel especially bitter when they discover

that the other party was treating them along purely as objects of monetary

calculation». Thus, misleading marketing practices once successfully

implemented can become a source of consumer dissatisfaction over time, as

consumers learn and develop their marketing expertise together with marketers.

Getting financial benefits at the expense of consumers’ welfare due to

consumer’s inattention or limited knowledge in something can bring significant

losses to the company, once consumers gain persuasion knowledge in the

field.questions the study intends to answer are the following: What are the

potential and lost benefits, if any, for companies that use covert pricing

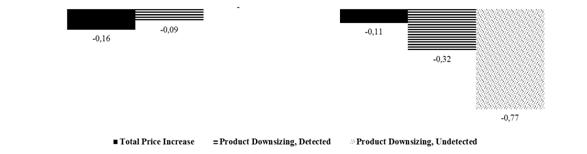

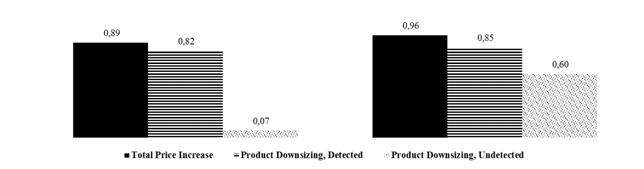

tactics as compared to overt pricing tactics? What are the impacts, if any, of